Recommender systems are everywhere. We receive our entertainment and information from algorithms that curate content according to our feedback. A multitude of proprietary recommender systems exist today, but for developers seeking to use them they are effectively black boxes. Developers can try to implement their own recommender systems, but there are a variety of challenges related to training and inference such as the network connection separating the ML algorithm from the data, and the need to efficiently update the recommender system's knowledge when a user expresses a new opinion about an item. I have created an open-source collaborative-filtering-based recommender system that integrates directly with the database, saving time and resources by eliminating the need to move data over the network when training or refining the system. It is implemented as a PostgreSQL extension, so it is easy to integrate with any application that uses a PostgreSQL database. It supports continuous learning, updating the model incrementally as users express their preferences. Its recommendation quality is near that of top performing entries in the Netflix Prize competition on that dataset.

Taking EECS 445 in November 2023 got me thinking about recommender systems. As someone who's frequently in the position of developing a backend for a website or app, I saw a couple collaborative filtering algorithms in class and thought, how would I implement this algorithm for my website/platform? My first thought was to simply run the appropriate ML training and inference steps on the backend server, but some major issues came to mind.

SELECT id, name FROM movies ORDER BY score(movies.id, {user id}) LIMIT 10. However, the database system has no idea how to calculate such a thing, since it doesn't have access to the model! So, I would be forced to instead select every movie and perform any sorting and pagination server-side rather than in the query, meaning I have to write significantly more code.So, I reasoned that the best way to implement a recommender system would be to have all ML done in the database. This way, the server can query the most highly recommended results without ever having to transfer a whole database's worth of data over the network. This is the idea behind Sveddy.

After some preliminary research, I figured out that Sveddy's functionality could be implemented as a PostgreSQL extension. This would allow me to write the recommender system in C and have it run directly in the database. It also would make integrating Sveddy with an existing application very easy for developers - they only need to install the .so file and then run CREATE EXTENSION. The extension would provide a set of new SQL functions exposing its core functionality.

initialize_model_uv function.train_uv function is responsible for this.predict_uv function takes a user's attribute weights and an item's attribute weights and returns the predicted rating the user would give to the item.update_model_uv function is responsible for this, and is added as a trigger to a model's source table (of user-item ratings) when it is initialized.

Sveddy is a collaborative-filtering-based recommender system. This means that it makes recommendations based on the preferences of similar users. The core idea is that if two users have similar tastes in movies, then a movie that one user likes is likely to be liked by the other user as well. The model is trained on a matrix of user-item ratings, where each cell is the rating a user gave to an item. Here what such a matrix might look like, where the row number is the user ID and the column number is the item ID.

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | |

| User 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| User 2 | 2 | ? | 5 |

| User 3 | 1 | ? | ? |

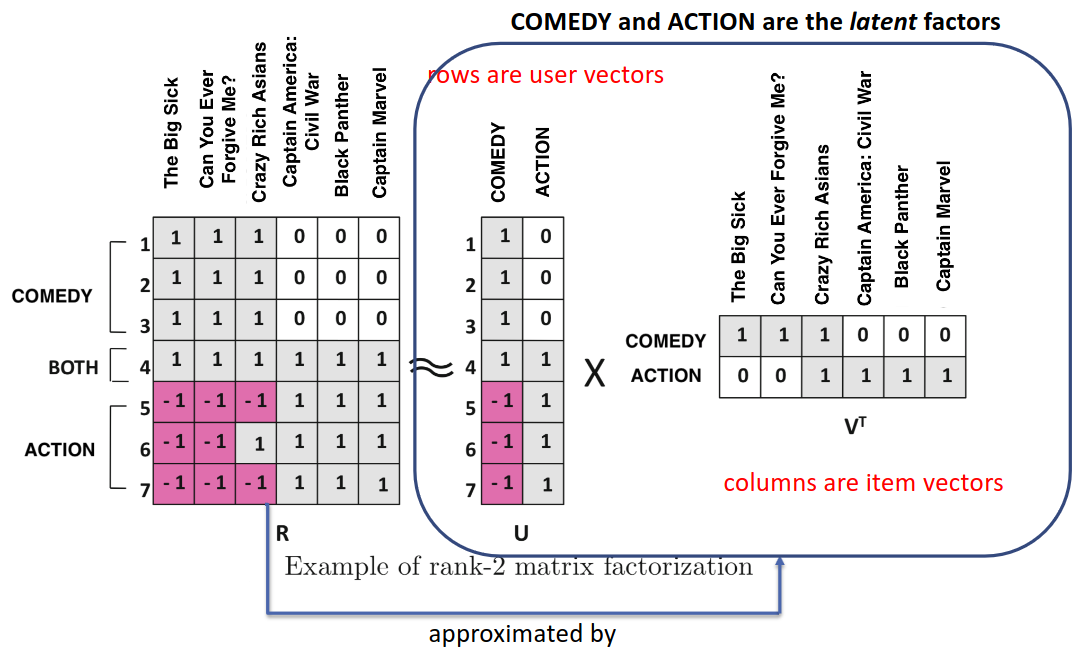

This matrix has many missing entries since not every user has rated every item. It's the model's job to estimate what rating a user would give to an unseen item to determine what to recommend. So, the task is to fill in this matrix. There are many ways to do it, but Sveddy implements a method called Funk SVD, attributed to Simon Funk in the Netflix Prize contest. This method posits that there are certain attributes about items (here, movies) such as genre, family-friendliness, amount of action, etc. that all movies have in varying degrees. Users have this same set of attributes, but the values represent their like or dislike for that corresponding attribute in an item. The rating of a movie by a user is the similarity (dot product) between the movie's attribute vector and the user's attribute preference vector. Here is how this matrix approximation would be constructed with only 2 attributes (comedy and action):

In the above diagram, to estimate the rating of item 6 ("Black Panther") by user 6, we take the dot product of the row of U corresponding to user 6 [-1, 1] with the column of V corresponding to item 6 [0, 1]. The dot product of these two vectors gives us the estimated rating of -1*0 + 1*1 = 1, which is also the actual rating. To train this model, we calculate the error between the estimated rating and the actual rating for each cell where an actual rating exists, and minimize the sum of squares of these errors by adjusting the values in U and V in alternating fashion.

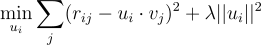

Most ML algorithms use gradient descent to minimize error, but here we can use coordinate descent because there is a closed-form solution for the ideal value of each row of U and V. So, we'll alternate between optimizing U and V. Suppose we optimize U first. The objective function we want to minimize, for each row ui in U, is:

To clarify things here:

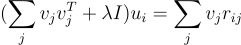

Setting the gradient of this with respect to ui to zero, we can solve for ui, and after some calculation, this is the resulting matrix equation:

After solving this equation, we update all rows in U and then do the same process for all rows in V. We repeat this until the error converges to a minimum.

Because Sveddy is written as PostgreSQL extension, its main functionality is written in C, with some PL/pgSQL (procedural Postgres-flavored SQL) included as well. The C code uses the PostgreSQL API to interact with the database.

Initializing the model is fairly simple. We start by creating the tables to hold U and V, and initializing their rows' values to vectors of length k with random values between 0 and 1.

-- Create U and V

EXECUTE format('CREATE TABLE %I (

id integer PRIMARY KEY,

weights real[]

);', u_table_name);

EXECUTE format('CREATE TABLE %I (

id integer PRIMARY KEY,

weights real[]

);', v_table_name);

-- Fill U and V

EXECUTE format('INSERT INTO %I (id, weights)

SELECT %I, get_initial_weights_uv(%s)

FROM %I

GROUP BY %I;', u_table_name, user_column, k, source_table, user_column);

EXECUTE format('INSERT INTO %I (id, weights)

SELECT %I, get_initial_weights_uv(%s)

FROM %I

GROUP BY %I;', v_table_name, item_column, k, source_table, item_column);

Here, get_initial_weights_uv is a PL/pgSQL function that generates a random vector of length k for a user or item. After this, triggers are added for continuous learning, and the model is added to the table of models.

-- Triggers to update the model. Deletion trigger not needed because we aren't going to update weights on delete

EXECUTE format('CREATE OR REPLACE TRIGGER update_model_uv

AFTER INSERT OR UPDATE ON %I

FOR EACH ROW EXECUTE FUNCTION update_model_uv();', source_table, source_table);

-- Insert the new model into the UV models table

EXECUTE format('INSERT INTO sveddy_models_uv (

source_table,

user_column,

item_column,

rating_column,

u_table,

v_table,

k,

regularization_factor

) VALUES (%L, %L, %L, %L, %L, %L, %L, %L)

', source_table, user_column, item_column, rating_column, u_table_name, v_table_name, k, regularization_factor);

This is the most complex part of the code. First, metadata about the model is loaded, such as the relevant table and column names and hyperparameters:

// Load model parameters

sprintf(sql, "SELECT user_column, item_column, rating_column, u_table, v_table, k, regularization_factor FROM sveddy_models_uv WHERE source_table = '%s'", source_table);

ret = SPI_exec(sql, 1);

if (ret != SPI_OK_SELECT) {

elog(ERROR, "train_uv: Could not find source_table = '%s' in sveddy_models_uv", source_table);

}

user_column = SPI_getvalue(SPI_tuptable->vals[0], SPI_tuptable->tupdesc, 1);

...

Then, the model's U and V matrices are loaded into memory:

// Allocate enough memory for max_rows_uv linear equations

linear_equations_size = sizeof(float4) * (max_id_uv + 1) * k * (k+1);

linear_equations = palloc(linear_equations_size);

// Allocate memory for U and V

u = palloc(sizeof(float4) * (max_id_u + 1) * k);

v = palloc(sizeof(float4) * (max_id_v + 1) * k);

...

for (enum uv_table_which which = U; which <= V; which++) {

float4 *this_memblock = which == U ? u : v;

sprintf(sql, "SELECT id, weights FROM \"%s\"", which == U ? u_table : v_table);

cursor = SPI_cursor_parse_open(NULL, sql, &parse_open_options);

...

}

Then, the training loop is run. For each iteration, the U matrix is updated, then the V matrix is updated:

for (int training_iteration = 0; training_iteration < max_iterations && current_patience > 0; training_iteration++) {

enum uv_table_which which = training_iteration % 2; // Start arbitrarily with the u step, alternating

double total_square_error_train = 0;

double total_square_error_validation = 0;

...

// This query returns ratings from source_table along with the corresponding user and item ids

sprintf(sql, "SELECT \"%s\".\"%s\"::real, \"%s\".\"%s\", \"%s\".\"%s\" FROM \"%s\"",

source_table, rating_column, source_table, this_id_column, source_table, that_id_column, source_table

);

In order to solve the matrix equation mentioned before, in the form Ax = b, for the ideal value of the row x in U or V, we need to construct A and b. A and b are both defined in terms of sums over the opposite table from the one being optimized. The following code constructs A and b:

// A is at the beginning of each [A, b] block in linear_equations

// Clear A matrices, setting diagonal elements to regularization_factor

memset(linear_equations, 0, linear_equations_size);

#pragma omp parallel for

for (float4 *A = linear_equations; A < linear_equations + (this_max_id + 1) * k * (k+1); A += k * (k+1)) {

// Fill in the diagonal elements with regularization_factor

// diagonal elements are k+1 indices apart

for (float4 *element = A; element < A + k * k; element += k + 1) {

*element = regularization_factor;

}

}

// Now sum other components to A matrices and b vectors

cursor = SPI_cursor_parse_open(NULL, sql, &parse_open_options);

while (true) {

SPI_cursor_fetch(cursor, true, ROWS_TO_FETCH);

if (SPI_processed == 0) break;

for (int i = 0; i < SPI_processed; i++) {

float4 rating = DatumGetFloat4(SPI_getbinval(SPI_tuptable->vals[i], SPI_tuptable->tupdesc, 1, &is_null));

int32 this_id = DatumGetInt32(SPI_getbinval(SPI_tuptable->vals[i], SPI_tuptable->tupdesc, 2, &is_null));

int32 that_id = DatumGetInt32(SPI_getbinval(SPI_tuptable->vals[i], SPI_tuptable->tupdesc, 3, &is_null));

float4 *this_weights = this_memblock + this_id * k;

float4 *that_weights = that_memblock + that_id * k;

float4 *A, *b;

float error = rating - dot(this_weights, that_weights, k);

if (is_validation_row(this_id, that_id, validation_fraction)) {

total_square_error_validation += error * error;

total_processed_validation++;

} else {

// Add that_weights * that_weights^T to the right A matrix (TODO: SIMD)

A = linear_equations + k * (k + 1) * this_id;

for (int row = 0; row < k; row++) {

for (int col = 0; col < k; col++) {

size_t offset = row * k + col;

A[offset] += that_weights[row] * that_weights[col];

}

}

// Add rating * that_weights to the right b vector

b = A + k * k;

for (int row = 0; row < k; row++) {

size_t offset = row;

b[offset] += rating * that_weights[row];

}

total_square_error_train += error * error;

total_processed_train++;

}

}

SPI_freetuptable(SPI_tuptable);

}

The #pragma omp parallel for is an OpenMP directive that parallelizes the loop over the rows of U or V. This is a performance optimization that can speed up training significantly on multi-core processors. This part of the code also splits the data into training and validation sets and keeps track of the validation set RMSE, a statistic used to determine when the model is fitted. After constructing A and b, we solve the matrix equation for each row in U or V:

// Solve all linear equations, placing solutions into u or v

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int id = 0; id <= this_max_id; id++) {

float4 *weights = this_memblock + id * k;

float4 *A = linear_equations + (k * k + k) * id;

float4 *b = A + k * k;

if (isnanf(weights[0])) {

// This row has been deleted

continue;

}

// Compute weights

cholesky(A, b, weights, k);

}

} // end for

Here, this_memblock refers to the block of memory storing either the U or V table. The cholesky function implements Cholesky decomposition, a method for solving linear equations of the form Ax = b where A is symmetric and positive semi-definite. After solving for all rows in U or V, the model is updated in the database:

// Write results

for (enum uv_table_which which = U; which <= V; which++) {

SPIPlanPtr update_plan = which == U ? update_u_plan : update_v_plan;

int this_max_id = which == U ? max_id_u : max_id_v;

float4 *this_memblock = which == U ? u : v;

for (int id = 0; id <= this_max_id; id++) {

float4 *weights = this_memblock + id * k;

Datum *weights_datums = palloc(sizeof(Datum) * k);

ArrayType *weights_array;

Datum datums[2];

if (isnanf(weights[0])) {

// This row has been deleted

continue;

}

// Create array of datums from weights

for (int j = 0; j < k; j++) {

weights_datums[j] = Float4GetDatum(weights[j]);

}

weights_array = construct_array(weights_datums, k, FLOAT4OID, sizeof(float4), true, 'i');

datums[0] = PointerGetDatum(weights_array);

datums[1] = Int32GetDatum(id);

// Update row

ret = SPI_execute_plan(update_plan, datums, NULL, false, 0);

if (ret != SPI_OK_UPDATE) {

elog(ERROR, "train_uv: failed row update for %c table, id = %d, ret = %d", which == U ? 'u' : 'v', id, ret);

}

pfree(weights_datums);

}

}

This saves the weights into the appropriate row in U or V. The PostgreSQL API requires these to be assembled into a special kind of array, then into a Datum, to be passed as a query parameter.

The trigger function responsible for updating the model incrementally is very similar to the one that trains the model. However, instead of running multiple iterations, updating all rows of U and V until convergence, it only updates one row in U corresponding to the user and one row in V corresponding to the item. This makes it much faster than a full model re-train. However, after enough updates like this the model can become out-of-sync with itself, so re-training the model on a regular basis is best for accuracy.

Predicting the rating of a user on an item is a simple dot product between the user's attribute weights and the item's attribute weights. This is implemented in the predict_uv function, which takes the user weight vector and the item weight vector as parameters and returns the predicted rating. It would have been cleaner looking to take the IDs as parameters, but this would force the function to perform a lookup on the U and V tables each time it is called, when the more efficient way to do this is with a join.

/*

* Takes dot product of a and b, each of which are k-length.

*/

static float4 dot(const float4 *a, const float4 *b, int k) {

#if !defined(__i386__) && !defined(__x86_64__)

float4 sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < k; i++) {

sum += a[i] * b[i];

}

return sum;

#else

float4 sum = 0;

__m128 sum_vec = _mm_setzero_ps(); // x is four floats, initialized to zero

__m128 shuf_vec;

int i;

int simd_len = (k / 4) * 4; // Maximum length, chunked to four elements at a time, where each chunk is full

for (i = 0; i < simd_len; i += 4) {

__m128 vec1 = _mm_loadu_ps(a + i);

__m128 vec2 = _mm_loadu_ps(b + i);

__m128 multiplied = _mm_mul_ps(vec1, vec2);

sum_vec = _mm_add_ps(sum_vec, multiplied);

}

shuf_vec = _mm_movehdup_ps(sum_vec);

sum_vec = _mm_add_ps(sum_vec, shuf_vec);

shuf_vec = _mm_movehl_ps(shuf_vec, sum_vec);

sum_vec = _mm_add_ss(sum_vec, shuf_vec);

sum = _mm_cvtss_f32(sum_vec);

// Do the rest of the elements in case k wasn't divisible by four

for (; i < k; i++) {

sum += a[i] * b[i];

}

return sum;

#endif

}

PG_FUNCTION_INFO_V1(predict_uv);

Datum predict_uv(PG_FUNCTION_ARGS) {

// The function takes two arguments, both of which are real[].

// Returns the dot product, as a real.

...

result = dot(a_data, b_data, a_len);

PG_RETURN_FLOAT4(result);

}

Since this function is called once for each row, I was careful to make it as fast as possible. This implementation leverages SIMD to speed up calculating the dot product. This function is then called in a query like this:

SELECT predict_uv(u.weights, v.weights) FROM u, v WHERE u.id = 1 AND v.id = 2;

A more complicated example would be something like this, to show a user 5 movies they haven't seen before:

SELECT items.*, predict_uv(u.weights, v.weights) AS predicted_rating

FROM (

SELECT id, weights FROM ratings_sveddy_model_v

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT 1 FROM ratings

WHERE user_id = 3 AND movie_id = ratings_sveddy_model_v.id

)

) AS v

CROSS JOIN (

SELECT weights FROM ratings_sveddy_model_u

WHERE id = 3

) AS u

LEFT JOIN items ON items.id = v.id

ORDER BY predicted_rating DESC

LIMIT 5;

To test if the algorithm performed well on real-life data, I downloaded the Netflix Prize dataset and imported it into PostgreSQL. This dataset has 100,480,507 ratings from 480,189 users on 17,770 movies. I chose parameters k = 4 and regularization_constant = 0.05 for this experiment. Despite the large dataset size, choosing a larger value of k didn't help accuracy.

Initialization took 79s. I think most of this time was spent in the query that fills U and V, where the system must find all unique IDs in the source table and generate lots of random values for the initialization of U and V. The training process converged after about 6 minutes and 8 iterations. This time was about equally split between I/O (retrieving rows from disk) and compute (solving matrix equations). Inserting a new rating into the table incurred a continuous learning overhead of 450ms.

The RMSE on the validation set was 0.87, which is very close to the top-performing entries in the Netflix Prize competition (~0.85). However, it's impossible to make a truly fair comparison here, as participants in the netflix challenge had RMSEs calculated from a separate private test set (the "qualifying set"), whereas Sveddy's validation RMSE was calculated by separating out 1/8 of the public training data as the validation set. The main difference between these is that the qualifying set was made up only of recent ratings, whereas Sveddy's validation set is sampled randomly from the public training set. As much as I would like to know Sveddy's RMSE on the qualifying set, the Netflix Prize closed over 10 years ago and is no longer accepting submissions. Entries using similar techniques scored RMSEs around 0.89.

I'm proud of my work on Sveddy, but there are a few things I could improve: